Jim Self Interviews David Angel

Transcribed by William Nakamura

Day 1 – 9/1/20

Jim: This is an interview with composer/arranger David Angel regarding our new triple CD “Out on the Coast”. David, do you mind telling me a few things about your childhood, and then later on in your career?

David: I grew up in Highland Park, near Los Angeles. We had a piano in the house, and my mother gave all the children piano lessons. But when I took piano lessons with teachers, after the first day they would say ‘don’t waste your money, he’s no good for music’. So after that I taught myself to play, I loved harmony, and then when my mother and her sisters would play old Russian songs, I would play the piano by ear. Then I played the saxophone, worked in Latin bands throughout high school and my early college years playing saxophone or bass. After that I travelled around California, moved to Monterey for a while, met a wonderful woman, and we got married. After a while we moved back to L.A. and I went back to Los Angeles City College. Soon I got a letter from Paramount Studios’ music editor looking for someone to help him read music, so they sent me. He introduced me to David Rose, and suddenly I’m writing orchestrations for Bonanza. I quit school, kept working in TV, movies, and records for about 30 years and, while I was doing that, I was writing for my band.

Jim: You were playing jazz early too, as a sax player, right?

David: I learned clarinet playing in a big band, I played with Kid Ory and his Creole Jazz Band in the Beverly Caverns in L.A. because the clarinetist (I can’t remember the name) was sick, they were all New Orleans guys, anyway, he said ‘let the kid play while I’m in the hospital’. He had an operation, and I got to play for two weeks with Kid Ory when I was 16.

Jim: When did you get into Bebop jazz, and playing in bands around town?

David: Well that’s the subject, because LA was loaded with jazz and jazz clubs, and the style of west coast jazz was really strong. I grew up in it and I would drive to clubs when I was 16 or 17 and listen to all the jazz bands. I had a lot of records. So west coast jazz was my goal. Of course it never happened because there was no west coast jazz after the 50’s. But I absorbed it, and I studied with two teachers. Dave Robertson who was a great, great fellow (one of the first–other than Don Redman in the 20’s to write Big Band Music). Dave Robertson taught classical and jazz, and it was very proficient for me to study that way because I was into both a as a kid. Then I studied with Roy Harris, the symphonic composer. So that was my formal education, aside from some harmony classes.

Jim: Before you go on, the other day you mentioned something about a sort of timeline of people that had influenced you as a writer.

David: Oh, my first exposure was Jerry Mulligan and Shorty Rogers, Those two influenced me a lot, and they both wrote charts while I was already thinking that way. And Jack Montrose and Marty Paich–also west coast players and writers. Then I discovered Gil Evans, and in the arrangement I did of Loverman, I paid a little tribute to Gil in there as well as on other charts.

Jim: We’ll be getting deep into the tunes later.

David: I worked for David Rose on Bonanza and Nathan Scott on Lassie when I was about 21-22. In those days it was possible to do that–now it probably isn’t. I was just a guy who was sent over to Paramount to help an editor and, before I knew it, I was working. So then it went on for 12 years on live TV (with Jerry Lewis, Andy Williams and the list goes on and on)–all those live TV shows, and then it ended. I spent those years arranging for big band and orchestra in TV studios, and then I worked quite a lot in Film TV, dramatic shows. I worked for Maurice Jarre for 12 years as an orchestrator, but I would say in that case 85-95% of my work was composing, ghost writing or whatever you want to call it, and 10-15% was orchestration. He was a very good composer, but he had limits. So I was the one who wrote the source work (including a lot of the chases)–about 9 years of that ending around 1980, I guess.

Jim: So when did you start the band?

David: The band history goes back to the late 60’s. We started out in a club on Sunday afternoons and, after the club folded, we went to the union and kept playing all those years until now

Jim: Was the early band the same size?

David: The first band was two trombones, three trumpets and four saxes. A few years later we added a bass trombone and that went straight on for many years. Then in recent years (when Stewart Aptikar quit playing) I reduced the trumpets to 2. I didn’t want to replace him and then, when Bob Enovoldsen died, I didn’t want to replace him either, so I added a horn. Now the band is two trumpets, horn, trombone, bass trombone/tuba–and I made it 5 saxes, eliminated the piano. So the rhythm section now is guitar, bass and drums.

Jim: Well, you know I played in your band for a long time, first as a sub for Don Waldrop. He played a tuba/bass trombone double (there weren’t too many guys who did that). When Don left town you asked me to be a regular player. It’s been several years now, and of course it’s one of my great joys. Now the band has never really had a commercially available recording but think you said it’s only had one professional recording, is that correct?

David: We recorded every few years at Jim Mooney’s studio in Hollywood, but when Bill Perkins died he knew that if he gave me the recordings they would be lost in 6 weeks. So he gave them to a company in San Diego, and after some years we played a concert at LA Jazz festival and the producer, Peter Jacobson, who had all those tapes and just kept them, he came to that concert and heard the band, and said he was going to issue some of those pieces. Nobody got paid, of course, but he put them out there. I don’t know if you can still get it.

Jim: So this new recording project is more of a real production. It is going to be a triple CD with 22 of your charts. And we’ll get some radio and print promotion. It’s almost like a first album.

David: Yeah, it is. The last one nobody got paid, one of those things where ‘if you give me the CD I’ll put it out, but I won’t produce it’. I don’t think we sold more than 10 copies anyway.

Jim: I know the story, man! Before we talk about the players in the band and your writing, why don’t you say more about your career? So after the studio work slowed down…

David: The studio work didn’t actually slow down. The composers I wrote for wanted me to write for the synthesizer, and I told them I can’t write for what I don’t hear, it just doesn’t make sense to me. I don’t know what kind of sound would come out, so I said ‘I’m not gonna do it’. There is such a beautiful world beyond this studio business. About this same time (ironically) I got two letters–one from USC asking me to teach orchestration and composition in the film music program. The other letter was from the cultural minister of France. Billy Byers had been working in France, and they wanted him to teach at the Paris Conservatory because they didn’t have trained film composers, and they were making a lot of movies. But he wouldn’t teach, so he said ‘I know a guy’. So (right after I had just quit writing cues), I chose to go to France (of course) and they gave me a nice job. I ended up teaching in three schools, and I gave lectures to the teachers at the Paris Conservatory–which was a moment I wish my mother had been alive to know about because she revered that school. I taught there for 7 years, I did a guest teaching job in Switzerland, and I was so happy to be there. The guy that hired me liked the way I talked. So I went back to Paris, finished up the semester and went to Switzerland and taught there for 8 years–at four schools, mostly at Lucerne at the big music university and the one at Zurich. Then I decided to come back and they had me come for the next 5 years and I actually earned my living during those 3 months of the year. The rest of the time I was pretty free so I wrote for the band, and some of that is on the CD’s we’re making.

Jim: During all that time in L.A .you kept the band going

David: Yeah, when I would come home for vacation we would rehearse every week, so it wasn’t disbanded completely.

Jim: You’re currently doing some very intellectual teaching of theory, aren’t you?

David: I was giving a class last fall to composers in Hollywood. It was very nice—with a very good video, I was glad to be back with people who spoke English all the time. Bill Holman was there, and several other busy guys. Now what I’m doing is sending out problems to all those students. I give it to the one student who emails everybody. About every two weeks I set up a question ‘can you analyze this sound and then modulate it and then make an etude out of it’? My theory of teaching is simple: you have to start composing immediately, the first day. Composing is the first thing everyone has to do. I call it making etudes. It’s just a short piece, 10-15 seconds, which is a long time in music. I ask them to take a problem and a sound they want to study. In the modern age we don’t have chords and keys and scales, which used to be the basis for mastering. They aren’t there anymore. I made up a very simple approach, taking the harmony from ancient times, long before diatonicism and modality. That’s the basis of my teaching.

Jim: I wish I had had you as a teacher, I wish someone had told me to start composing when I was young! Before we talk about the guys in the band, would you tell me about your style (I’m talking about the jazz band, mostly). To me, you are a very unique composer–the way you write. And you write by hand by the way, which is fairly antique by now. But you also you write so uniquely. I like to describe your music as “Gil Evans meets JS Bach”–because of the polyphonic nature of your music. Would you describe your writing?

David: I’ll have to disregard that elevated position(laughter). It’s ironic that the way I write comes from a certain way. I started writing as a kid. I wasn’t aware that it was special, I just liked it. I would sit at the piano and play things, but after a while I would write charts for Latin bands that I was playing with in East LA and learned how to voice things a little bit. Then I went to West Lake College (the first jazz school in America before Berklee) and studied with David Robertson there. I learned how to voice the band you know, the fundamental block harmonies and what not. But what influenced my style at first was the west coast style–and second my love of classical music. I grew up with it–we always had it in the house. Every night my father would listen to classical music. And then what took place was, I began to write film cues. A cue could be 8 seconds, or it could be as long as 3-4 minutes, even longer sometimes, but the idea of a cue is that you ar–mood and action. But then something changes so the music changes. Being able to make transitions and segues was kind of the art of cue writing, making it so no one notices the change.

How this influenced my style is simple. I was writing and I had been writing episodically. I had spent my life learning how to write music that changed every so often. If you are walking down the street and somebody walks out with a gun, the music changes. So now these pieces on this CD reflect that. The piece can go on and with a small transition it enters into another mood completely. Now, I know there are some aficionados out there who say that’s not jazz, and you shouldn’t write like that, but on the other hand, that’s my way. So even if it’s wrong, it’s still my way, I still think it’s jazz, but not the popular kind of jazz today.

Jim: Those elements explained a lot to me. The guys in the band are always amazed at how contrapuntally you write things. I know Bill Holman does that as did Gil Evans and a few other people. The band just loves your music so much, because it’s challenging. It’s pure jazz but you have to be a pretty good classical player to play it well. It has classical elements, and it’s packed full of solos.

David: The sound is everything! So being a lover of classical music had a big influence on the way I approach these pieces. Many years ago I became more radical, like 40 years ago, probably writing more far out music. But as I got older my refinements take over, and I began to appreciate tonality. As you know from the voices, sometimes I like to move the sound close to dissonance without creating a dissonance, and a lot of my music is what I would call absorbed dissonance, not reflected dissonance. And that skill (or whatever you want to call it) with voicings and harmony is the key to everything in my writing and, as a jazz musician, it is voice leading. I don’t think anyone in the band would criticize the way I write voice leading–it’s all natural and singable. I don’t sacrifice voice leading, ever! Anyway, the style is built up from Jack Montrose who was a very contrapuntal writer and wonderful musician from back in the 50’s and it meant a lot to hear him talk about principles of composing, not that I would call what I do principles. Other influences were Marty Page, Bill Holman, and Claire Fischer.

Jim: You want to continue about your writing style?

David: The main influence I got from cue writing for movies or television is the way I would write when I’m sitting at my table, I don’t have a piano. Now I’m old enough I wish I had a piano just to play, but when I was writing, the piano was the kiss of death, you sit there and you waste time and you lose your job. So I always wrote without a piano and I still do. When I sit at the table I am writing with a pencil and paper the same way I did all the years I worked and all the years I wrote for the band, so the things that come to me are more fluid. In other words, I just move in and out of ideas and turn the page. When I was writing cues I would turn the page and the copyist would run over and grab it. I didn’t have a chance to study what I was writing, and look back in that sense. And then did that when I was working away from the studios. In the later years I was working from home. I just got in the habit of drawing and turning the pages and moving on and then changing moods. I think Kim Richmond said my music is more emotional, and it didn’t occur to me until he said it, but then I listened to the CD, and there was an ‘openness’ allowing feelings to pour in, that maybe other writers don’t do and I could never do when I was writing for live TV and doing arrangements for singers and dancers.

Jim: Well you know something, being on your band, listening to these albums and CDs really opened me up to your writing. For the mix, one of the things you told us to do is bring out the backgrounds. Most of the big band writers, (we’re kind of a little big band–not a big big band), basically have the backgrounds in the background. You wanted us to bring it out so it sounds more like duets or however many players are playing. That’s kind of an unusual way, but it helps the counterpoint you’re writing. I was amazed at the result!

David: To me the background is part of the solo. I didn’t just write it to have fun. I write it because I think at this point in the solo it would be nice to feel a warm glow of harmony under it, and in the room where we play, every note in the background is clear, and every player gets something out of it. I write a background for the player, not just to keep writing charts. The background has to be clear and in the foreground complimenting the solos.

Jim: Once we remixed this stuff per your suggestions it just changed the character of everything. I probably know your music more than anyone else in the world, except you. (Well, really me and Tom–Tom Peterson who helped with the mix). The band has been made up of the “Who’s Who” of jazz players in Los Angeles for the last 50 years.

David: Since the late 60’s, yeah.

Jim: I of course got to know some of them like Bill Perkins, Bob Cooper, and Bob Enevoldsen, but most of them have passed on. Why don’t you name a few of the more prominent people we can draw attention to?

David: Jack Montrose, I transcribed his arrangements as a kid, and then he came back from somewhere and played in my band for 3 weeks on his vacation, which was a thrill. Another one was Herb Geller who I used to listen to–a West Coast guy–and he came home and played in the band. But then the trombones were interesting. We had Britt Woodman, Garnett Brown, George Bohannon and Bob Brookmeyer played in the band at the same time as Billy Byers. It goes on from there, Bob Payne, of course, was there for a while. Milt Bernhart played early on, and Herbie Harper played for a while–then Eno came. Conte Condoli played in the trumpet section for a couple of years, and his brother Pete Condoli was his sub. One of the great studio trumpet players, Uan Rasey played in the band for a couple years and loved the band. He would call me up at night and tell me how much he loved it, and I was honored that someone of that stature loved it. He was a great lead trumpet player. Marty Budwig played bass, Chuck Flores was the drummer for a while, and also John Guerin.

Jim: Well I remember Ron Gorow, Stu Apticar and Stacy Rowles.

David: Oh yeah, Stacy played for a long time. After Ron died, Stacy took over. Oh, and Betty O’Hara played trumpet in the band. And then when she was sick Stacy took over and stayed there for a long time.

Jim: How about saxophone players?

David: Oh, well Bill Perkins came in the band because Bud Shank was playing. Bud got so busy he was sending him as a sub, and one day Perk said ‘I’m the regular guy, Bud’s too busy and he doesn’t want to keep calling me, so I’m gonna play’ and he played alto for a long time. At one time the sax section included Bill Perkins, Bob Cooper, and Art Pepper.

Jim: Art Pepper–Wow!

David: Well he used to play in the band for two years on tenor, and Perk used to play alto. Art would say ‘why am I play tenor and Perk’s playing tenor when he’s a tenor player and I’m a tenor player?’ And I would say ‘well I love the way alto players play when they’re basically tenor players. I prefer alto players who play tenor.’ and that was the reason. Art was a great sax player, didn’t matter if he was playing alto or tenor. I can still remember the fours and eights between him and Bob Cooper. They were so magical you couldn’t tell where one began and the other ended, it was so incredible. I wish we had recorded the band with Art, but we didn’t record for a number of years, and it just worked out that he wasn’t there during that time.

Jim: I think Pete Chrislieb played at one time and also Gary Foster?

David: Gary played over the years, many times–on every chair except baritone.

Jim: And of course Kim Richmond (who was the Tonemeister on these sessions)

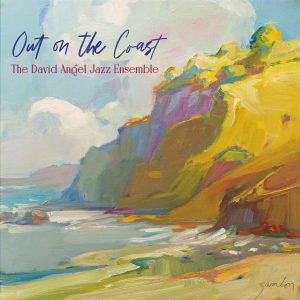

David: Kim of course has played a lot. And it was his wife Chris Zambon who painted the beautiful cover.

Jim: So, who played in the rhythm sections? Right now we have John Chiodini, guitar, Susan Quam, bass and Paul Kreibich, Drums.

David: Charlie Meyerson played guitar with us for most of those years, and John Bannister played piano–what a great soloist he was. Victor Feldman, and even Claire Fischer would come in as a sub when I needed him. So it was always somebody wonderful on piano.

Jim: Well one of the cool things is that I’m a tuba player, and very few people write for tuba, Gil Evans was notable for it with Miles Davis, and in the things he wrote, he used tuba a lot. My teacher, Harvey Philips was his tuba player for part of that time and Bill Barber did a lot of it too in New York and later Howard Johnson played in his band. Marty Paich wrote for tuba too. I was in his Decktette–a wonderful experience for me! I got to know Marty very well. But there aren’t too many guys who write for tuba in jazz bands, but I guess you learned to like that sound, right?

David: Well, I love conical bore instruments. The tuba is really a large cornet. It’s a beautiful sound down at the bottom. The cornet, you know, is a conical bore that blends well with the horns, once in a while I would be asked (which was very rare), ‘what instruments do you use on a cue’ and I would say ‘four horns and a tuba’.

Jim: When the guys play Flugel Horns I tell them that they are in MY (tuba) section. Well the brass in your band as you have it now, is really a brass quintet–standard brass quintet.

David: What a beautiful performance you all get out of that. When I listen to the CD, I just think, how could five guys get such an absorbing blend like that? Usually it’s bright and reflective, but these guys and you were able to blend and pull the sound together in what I call ‘absorbance’, in other words, one sound.

Jim: It’s the music that drives us, believe me. We’re all good players, but when we get good music in front of us, we get fired up. The current band is Jonathan Dane and Ron Stout on Trumpet/Flugel horn, the Trombone player is the great Scott Whitfield. Stephanie O’Keefe is our Horn player. It’s an amazing section and everybody gets to Solo. We’ll talk about the music in a minute, but it’s so unique. The saxophone players all double on flutes and clarinets.

David: They like it. You had to be that way because if I wrote for flutes and clarinets and they say ‘oh, I gotta play the clarinet’ then they shouldn’t be in this band. I think it’s a wonderful thing to have Sax players who can play beautifully on their doubles.

Jim: That’s the tradition of this city, in studio work, was doublers.

David: The great ‘Musician’s Musician’ Gary Foster, once said on a ten, ‘the requirement of the orchestra is to hold the music up’. (laughter)

David: I remember he influenced me to always keep things readable–as close as I could. You know, not everything in the band is sight-readable, but I would say the vast majority of it could be read and not scuffled over. And of course, that has to do with subs, but it also has to do with the regulars listening, so they don’t have to scuffle with note by note problems.

Jim: One of my problems playing in the band is there are frequent solos. I get lost in the way these guys are playing and sometimes I forget to come in after a rest!

David: Oh yeah, it’s happened to everybody. When a solo is going, a couple of guys will still be listening after they’re supposed to come in, that’s a tribute to the soloist.

Jim: Speaking of doublers, one of the greatest players of all time, maybe the greatest woodwind doubler in the studios, Gene Cipriano “Cip”, is a member of the band.

David: Yeah, I was saving his name for last.

Jim: We’ll talk about him in a second, I want to talk about the whole section. Right now the lead alto is Phil Feather and the second alto is Gene Cipriano. The first tenor is Jim Quam, and the second tenor is Tom Peterson, and the bari-sax is Bob Carr. I think I’ve mentioned all the people.

Day 2 – 9/2/20

Jim: One of the things we didn’t do yesterday was get a timeline of jazz composers that influenced you.

David: Don Redmond was the teacher of Benny Carter, Duke Ellington, Fletcher Henderson, and a few others, and those guys were the matrix that spread arranging out to jazz, so it comes from Don Redmond originally who started the idea of a big band. He put the saxes in front of the trumpets and trombones. I think Claude Thornhill had some good arrangers. Jerry Mulligan wrote some things for him, and Gil Evans of course, became well known as his arranger. I was mentioning yesterday that I put a little Gil Evans touch in the Loverman chart because the first time I heard the tune was the Gil Evans arrangement for Thornhill. But then the ones who influenced me the most were Johnny Richards, Jerry Mulligan, Gil Evans and Duke Ellington–who set the mood for all jazz arrangers to stretch out, and he really stretched out in the 20’s and 30’s. Some of those old recordings are beautiful. Yeah, Duke and Billy Strayhorn were influences. Billy’s ballads really had a big effect on me. Other influences were Bill Holman, Claire Fischer and Marty Paich. Here in L.A. I was able to hear them play their music.

Jim: I don’t know Don Redmond, but I do know all the rest.

David: He was actually a black man who was such a great musician as a kid that he got to go to the conservatory back then. He learned a lot about classical music, and he taught the chords of Debussy and Ravel to Duke Ellington and Benny Carter, that’s how they got their sound.

Jim: How about George Gershwin?

David: Well of course he’s a song writer, beautiful songs, but I think everybody grew up on Rhapsody in Blue and the Concerto in F

Jim: I think Ferde Grofé did those charts, didn’t he?

David: Well he takes a lot of credit–he’s the kind of guy that just couldn’t get enough credit. He put it on score, but Rhapsody in Blue was finished by George Gershwin, all he needed was someone to put it on score, and that’s like a copying job, you know?

Jim: Well you brought up something else, you also have sort of a timeline of classical composers that influenced you, that goes way back to Greek times, but particularly the impressionists. I hear it especially in Wild Strawberries and Love Letters to Pythagoras.

David: I grew up loving Ravel and Debussy. I first heard La Mer when I was a teenager and I never turned back. I heard Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring when I was a teenager and I thought somebody had dropped an orchestra out the window! It sounded like chaos! Of course, now it’s very tame and I know the piece, but oh when I first heard it on an old scratchy LP, I thought the orchestra was being poured out onto the streets. But now I understand what a masterpiece it is.

Jim: Well Stravinsky also had a neo-classical period where he wrote sort of jazzy things in the 20’s. The Octet comes to mind.

David: The Octet and the Symphony for Winds were written while he was in Switzerland, so he was writing for chamber groups. Those two pieces were played and the History of the Soldier was just before those. In the 20’s and 30’s, he wrote Apollo and Symphony of Psalms. They were called neo-classic because reviewers didn’t know how to deal with it. He was accused of betraying himself–that’s how stupid reviewers are. His answer to them was ‘I’m growing, and you can analyze the direction I’m growing in, but you can’t accuse me of something just because I’m growing into a new style. That’s what I’m doing, and that’s what you should have observed, not criticized me for not writing another Rite of Spring’.

Jim: How about some others, like Darius Milhaud

David: Oh yeah, I loved his music. I used to listen to it all the time. I think he liberated me in a lot of ways, he was so free, he improvised so easily on paper and for a guy like me who wrote cues, that’s an inspiration. I remember his piece called Six Little Symphonies, it was six short pieces, the whole thing together lasted less than a half hour. It was just improvisations–like Andre Duteaux in Paris during the 60’s-90’s. He wrote a lot of small works as well–some beautiful chamber works. I was influenced by him as well because he was, in a sense, writing atonal music, but he had it under control. It wasn’t just a row of notes, it was true composition with chromaticism.

Jim: What about Eric Satie?

David: Of course everyone should love him, because he represents calmness and serenity.

Jim: Well, didn’t he lead to the impressionists?

David: There was a debate between him and Debussy between who came up with the idea first. They were close friends at first, Satie was playing his little piano pieces at a bar called Le Chat Noir in Paris, and Debussy would go there and listen to him. He was like a cocktail pianist, but he was playing these original little pieces. Later, Debussy said ‘no, you didn’t influence me’ and it hurt Satie who thought he did influence him. Then, in the 20’s, when they had Les Six (the six composers) in Paris, (they were a show, you know), they put them together, and they took a seed catalogue and made an opera out of it. They made Eric Satie their hero, so as an old man, he was suddenly thrust in the foreground as the model and the hero of those French composers.

Jim: So many composers, including Bill Holman, were influenced by the string quartets of Bela Bartok, did you have any connection with that, or did that influence you in any way?

David: During the time in the 60’s, almost every jazz musician had a Bela Bartok string quartet CD in their home, if not all of them. It was very common to listen to that because of the jazz phrasing in Bartok. The young players at that time were in a world that was so different from this one–they loved music, and they didn’t care if it was jazz–they were listening to all kinds of classical music. Everyone I knew was listening to classical music, and Bartok was the favorite because of his phrasing and his chromatic twists and turns–and his melodies. I would say the misinformation was that he was influencing, I don’t think he was, I think he was appreciated. The modern jazz musicians felt the swinging elements in this music, but I don’t think he influenced anyone I know of, but there was a great popularity of Bartok among jazz musicians in the 50’s and 60’s. I loved it! I was listening to all his quartets, and the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta–all of these swinging pieces.

Jim: My favorite orchestra piece, which is much more conservative, is the Concerto for Orchestra. I think it’s a beautiful piece of orchestration.

David: Oh, it’s wonderful.

Jim: What I mean is it uses musical elements so efficiently.

David: Well it is conservative in the sense that he was dying, and he decided that since Koussevitzky gave him $10,000 to write it ‘I have to live now, in order to earn that, I have to write it.’

Jim: What a piece of luck that was for music

David: yeah, he was ready to die, but then he woke up and wrote that and the later the Viola Concerto.

Jim: One more question regarding classical music, the big fight of the 20th century was between tonality and atonality, and Bernstein concluded that tonality would win out because it was a part of nature. How do you come down on that argument–which I think you’ve thought a lot about? Your music is tonal, sometimes modal, you may have dissonant elements, but it’s tonal.

David: My attitude when students talk about these things, I say ‘be able to write tonal music, and then inflect dissonance, but the amount of dissonance is in your control’. In atonal music it’s out of your control, but when you inflect dissonance you inflect a particular dissonance for a particular sound, you are in control of the amount. And that is the key word, the amount of dissonance that goes into my music is very controlled, that’s why it doesn’t sound atonal, but there are a lot of chromatic elements. I believe you can write with the full chromatic spectrum, but you don’t have to write all the notes all of the time. There are some very beautiful “atonal” pieces. Lutoslawski wrote some gorgeous symphonies using 12 tone methods, but he compressed them so they weren’t like the German composers. He pushed them into particular sounds. We live in an age where mastery is not capable of being achieved as a composer unless you are determined to work in a particular way, because the general rules that used to be the basis for mastery are gone, so now you have to find your own basis. What I teach is tonality, but not the tonality that has been popular for the last 300 years. That style is the diatonic style and most people think that is tonality. They don’t know that thousands of years before that there was tonality, that tonality is simple, pure and to answer your question, it’s a part of nature. When water drops on a hard surface, I hear pentatonic tones.

Jim: Exactly, that’s why I was so lucky to play on Close Encounters of the Third Kind. With those five iconic notes that John Williams and Spielberg game up with and communicating between earth and aliens by peaceful means like music, and the fact that music is universal, and the pentatonic notes in that thing. That was one of the most important moments of my life–and I am so proud that the tuba was a part of that.

David: I think the whole world was proud of you for that.

Jim: Well, anyway, I don’t want to talk about me. I want to get into the music for the band and ask you two questions before we get started on that. For the album I need short little things for each song, but in the long run, I do want some elaborate things. What would you prefer?

David: I’d rather give you something short you can use, so give me a name and I’ll give you a sentence.

Jim: Before we do that, can you give us just a couple generalizations. There are 3 CDs, we’re going to talk about them in order. There is a huge variety of music on here. I have my favorites, but they keep changing. Of the 22 songs, approximately 1/3rd of them are your arrangements (by well-known and important composers). We’ll talk about when we get to them. The rest are all original things. Much of this music is fairly new, which shows off your recent writing, which you are doing daily, and then there are some things from as far back as the 70’s.

David: I think Ah Rite! is one.

Jim: And then are some pieces from 15-20 years ago.

David: Most of the pieces that are original have been written recently, that was a partial decision.

Jim: They really show your growth in the way you weave things, which is a hallmark of your music. Now, the album is called “Out on the Coast”–that’s sort of the theme of the album too–you live on the west coast, you were influenced by the West Coast Jazz scene. There are two tunes on this album, which you call Out on the Coast, but you wrote four of these, didn’t you?

David: I think there are four Out on the Coast pieces in the book. The tune This Time The Dream’s On Me I would call a “West Coast” arrangement. Out on the Coast is the term we use to identify arrangements or compositions that I have written consciously in that direction–the style of writing in the 50’s. I’m not trying to imitate it, just do something like it, because I’m still writing the way I think I should write.

Jim: Why did you choose 2 and 3, rather than 1 or 4?

David: well, I just had to pick something. We couldn’t do all of them and still have the long pieces to do.

Jim: What is the connection between them?

David: The connection is the “West Coast” style.

Disc 1

Jim: Let’s proceed with brief comments about each tune, and we’ll start with Disc 1, in order. 1st is Out on the Coast 2, an original by you.

David: It starts out with a saxophone trio that was written when we used to play trios at Bill Perkins house, Steve Kravitz and Bill Perkins and I played trios for seven years in his garage, so that’s one of the trios, and that’s what starts the first piece. That trio represents 200 trios that were written, at least according to Steve Kravitz there were 200 saxophone trios. Then it goes into a song that, the melody was written back in the late 70’s, early 80’s, i think the arrangement was written later, but the melody is from another arrangement that I had written that was lost, so I kept the melody and the chords. I also used that melody in a piece I wrote for Cello and Orchestra called A Rhapsody of Songs.

Jim: As we go through these, I’m going to mention the soloists.

David: The solos were, without question, beautiful and brilliant to listen to, all of them.

Jim: Some of them have many different soloists on them. Ah Rite! is like a study on how to play the blues. Anyway, the next one is Wig, another original by David Angel.

David: I don’t have a big story about that one, but I had the feeling that I wanted to give was very successful. Not every chart I can say is completely successful, but I was very happy with the feeling in Wig, I couldn’t describe why I wrote it except i was looking for that special feeling between Latin Jazz and even Pop, there was some place in that I wanted to get, and I think I did. I think the feeling in that is great.

Jim: Alone Together, which is your arrangement of the famous Arthur Schwarz piece.

David: There’s one successful place in that chart that I love–it’s the bridge just before the trumpet solo, a 16 bar transition bridge that leads to the trumpet solo. I thought that was really successful in the way that came out.

Jim: It was, it’s such a beautiful thing, and the soloists are great.

Jim: Track 4 is Lilo Vache. You might mention something about the titles of these if you want.

David: This one is a story. Lilo Vache literally means ‘the cow island–the island is in the Seine, in Paris, next to Ile de Cite, the island that has Notre Dame. In the old days the monks had to have milk and butter and everything, and they had a cow, and they had room for grass to grow, so the cow would live on the island and eat the grass and give them dairy. So that’s the basis for that name, but the story is I wrote this piece after I left Paris, I lived there seven years, and then I moved to Switzerland and decided to write a piece about my time in Paris, and that’s Île-à-Vache. The intro, which is very distracting for some people, is because I identify myself with the bari-sax, I identify the cow with the trombone and bass, and I identify Paris with the rest of the instruments coming in.

Jim: I guess a certain amount of your music is programmatic.

David: yeah, it was really written like that, and then when we get to the tune, from then on it’s a straight mambo, real Latin, I have to comment on John Chiodini’s solo from that tune–it’s a symphony. It’s so beautiful the way he plays line, and then when the background comes in, he starts playing chords and strumming, and it was so incredible what he did (singing), he did a great job, it was beautiful.

Jim: Prelude to a Kiss, your arrangement of the great tune by Duke Ellington. This features Gene Cipriano (Cip) on alto.

David: that’s all I can say, I thought Cip would play that beautifully, and I wanted him to be part of the soloing, so that’s where that came from.

Jim: What a joy to have him in the band at 92, I believe.

David: I think Stephanie O’Keefe said to me that ‘everybody thinks that they’re Cip’s best friend’

(laughter)

Jim: Well that’s the way he is!

David: That’s how he appeals to people

Jim: These are sidelines of course, but yeah, we love him. I’ve played with him since almost the first recording job I ever had in LA–and what a great Oboe and English Horn player he is, as good as any classical player.

Jim: Anyway, let’s go on, the next tune is that blues you wrote, I think in the 70’s, called Ah Rite!

David: it’s a jam session, and what I was doing, which is kind of strange, is I used to play with John Magruder’s band on Wednesday nights, and I would come around 3 o’clock and I would sit around his dining room player and write a chapter of Ah Rite!, and then Ron Gorow would come and copy while I was writing, and that night we would add that to the chart, and over a period of over two months, I think it was Ron one night when were there he said ‘aren’t you ever going to finish this chart?’ And I wrote the ending, right then and there, with the two-part ending.

Jim: It’s so swinging this tune, just the rhythm and Paul is just so dynamite on this. (I played a lot on John’s band)

David: I think the band was laying for that. It’s the one straight ahead big band chart on the CDs. Doc Severinsen wanted me to write something because I had written for a gospel group on the Tonight Show, and I brought that in, and he said ‘David, you know there’s a little old lady in North Dakota sitting in bed and watching The Tonight Show, and you want her to listen to this abstract jazz tune?’ He said ‘we can’t play it’. So that’s the story of ‘Ah Rite!. It was intended to be a compendium of blues.

Jim: One of the interesting things about this chart is that is two tunes on this album–you’re a great tenor player, and you play tenor with the other two tenor players, sort of a mash-up where you’re trading fours. Several of your tunes feature tenor duos, or dialogues, and this time you play, which is a very interesting part of this tune.

Jim: Now, let’s go on to one of my favorites, Wild Strawberries, which is one of your longest tunes–and it’s amazing, complex, and interesting.

David: It was written in Switzerland, after one of the most beautiful days I’ve ever had. I lived there for 8 years, and this was a day where everything conspired to be just perfect. I was hiking up a hill on the trail, a little narrow trail, and I didn’t bring any water or food. I was getting thirsty, it was the middle of the summer, but then I hit a plateau, maybe 60 feet level and then it goes up again, and it was covered in wild strawberries, and I was able to eat these strawberries and get my fluid. It was a great moment, and then I was coming back and I went through the wheat fields and the wind was blowing and the wheat looked like an ocean–you know waves of water. It was such a beautiful experience I sat down when I got back to my little room and started writing this piece.

Jim: I wondered if the title came from the great Bergman film?

David: No, it came from wild strawberries in the mountain.

Jim: Let’s move on to Hershey Bar, which your is arrangement of the Johnny Mandel tune. Luckily there’s a tuba solo in this one, and you’re playing tenor on this one as well.

David: Yeah, Jim Quam told me he wouldn’t play, so I had to play, he was forcing me to play. Johnny Mandel died just before you were going to let him hear it. It’s too bad he couldn’t hear the arrangement. I don’t know how he would have arranged it, but… Yeah, I don’t remember if there was any reason why I wrote that other than that it’s one of my favorite tunes to play. It has a beautiful bridge, but there’s no real story there.

Disc 2

Jim: Okay, that’s the end of the first CD, we’re gonna move on to disc 2, which starts with Between, which I think is one of your favorites and a recent piece.

David: I’m not gonna go through it all, but I know the word ‘between’ in many languages, not that I speak all of them, but I like that word. What I tried to do there was make a two feel, and I had to explain it to the rhythm section so they wouldn’t break into four later, which is normal, but I said ‘I’d like to have this all in two from beginning to end, and see if we can create a sound and a feel that is between two elements, without knowing exactly what they are. For instance, you can say between jazz and classical, but it’s not like that. It’s just an in-between feel that–I live in this in-between, I live at the walls of the city, and I kind of live one step in and one step out. It’s an attitude of mine. I would say it’s one of the most successful tunes in the book.

Jim: It’s a brilliant mix. It stands out.

David: I think that’s one of Talley’s best on the whole CD

Jim: And the next tune is Jimmy Davis’ Loverman, which is a famous jazz standard, and it features our great tenor player, Tom Peterson.

David: I had to do something for Tom, he’s such an outstanding artist on the Tenor, and the little reference to Gil Evans was intentional. Like I said, I first heard that song from Claude Thornhill’s band with the Gil Evans arrangement, and I took a little piece of that and put it in there.

Jim: But of all the arrangements on this album, every one of them is a classic, how else can I put it? Classic jazz tunes that everyone loves and respects.

Jim: The next tune is another new original by you, called Leaves.

David: This is the one where I had trouble deciding whether to put in a cumbiata, remember that one? I knew there were time problems, and I went back and forth, and finally when you told me about the time I realized that this one would fit better because it was shorter. I had no intention of recording this, but it has one characteristic that is worth noting, which is it is the last thing I wrote for the band.

Jim: So far! I am so glad we recorded it—great feel and wonderful solos!

David: Yeah, so far. I wanted to write something in three, but not have it be a waltz constantly. There are some sections that are a waltz, and jazz waltz feel, but I wanted to write a piece that was in three, and didn’t have to feel like a waltz all the time. I think in some ways it was successful.

Jim: You prefer ¾ swing or a ¾ waltz rather than jazz waltz, don’t you? Most of your ¾ stuff is like that.

David: yeah, they’re not really waltzes. There was one other thing about Leaves, it came to me in a moment as I was sweeping the driveway. The wind came up, as it often does the long driveway, and it was like a whirlwind, and it picked up the leaves, and sent them into the air, and it seemed to me that they were in three. They were going this way and then that way, and then over there, and so that’s where the title came from. It felt like that.

Jim: Let’s move onto another ballad on the album, which is a Billy Strayhorn’s tune called A Flower is a Lovesome Thing. Your arrangement features our wonderful horn player Stephanie O’Keefe.

David: Well, one thing is that the tune itself intrigued me. It was so unusual for a ballad. The harmony was odd, which often happens in Strayhorn. And that intrigued me, made me want to see if I could make some sense out of it in my way, but the other part was the French Horn melody. I thought ‘what a challenge for a horn player to play that line’ I thought ‘Stephanie will make chopped liver out of this thing–she could do that all day long–and she did, She really played that beautiful chromatic line. It was basically written for her.

Jim: One of the things I find satisfying about this album is you feature everyone, not just once but many times, and that’s what makes it a jazz band to me, and thank for you liking the tuba giving space to be a soloist too. Now we’re going onto another original by you that features Ron Stout on the trumpet.

David: Oh, I wanted to mention Ron is on the band too. Deep 2 features Ron Stout. He plays flugel horn mostly, but this was a trumpet solo.

David: I’m trying to remember what caused me to write this. I was looking for a feel that wasn’t typical jazz, but has some roots. The roots of this tune are in Duke Ellington (with the toms and the snare off, and using mallets). I wanted to have that effect of the tom-toms and the mallets going through the whole piece, effecting everything. And it did, it worked out very well that way. And of course Ron Stout, he doesn’t know how to play a wrong note. He is featured on this piece.

Jim: sitting in front of him in your band is one of the joys for me, because I want to play like him when I grow up!

Jim: So, going on to another one of your longer songs, a mixture of slow and fast, it’s an original called Moonlight.

David: When I wrote this I was in an old Swiss house at the very top floor, almost an attic, but there was a room up there. The room was just the perfect composer’s room–just a little room with a round table and one chair. I would sit up there and I could see over the top of the houses nearby because it was so high up. One night the moon was shrouded and I heard the part that’s played by the two alto flutes and the clarinets and I built the piece around it. The form, as often happens in the charts I write, goes into a faster tempo and, around the same time I was thinking to double the tempo The moonlight is in the woodwinds, and the double tempo is what you do in moonlight, so it was like nighttime jazz.

Jim: There are four longer songs that are ballads in this CD, and it’s hard for me to pick out the favorite. Every time I hear it they keep changing–and I think that’s a great sign.

Jim: Okay, so we’re going to move on to Out on the Coast 3, which is the 3rd of those 4 that you wrote.

David: I told you about the letter Mozart wrote to his dad that said ‘what’s worse than one flute is two flutes’. So I decided to write this. My friend in Switzerland, a great clarinet player and wonderful man, Johannes, said he hated the flute, he couldn’t stand to hear it. Something in his ear caused the flute to be harsh. As a joke I wrote the two flutes for him. Maybe I was trying to show him that two flutes could sound good together–but in the West Coast style, because he liked that style.

Jim: Well it’s another one of your masterpieces.

Jim: The next tune is Autumn in New York, the Vernon Duke standard that features Phil Feather and Ron Stout. I love this one too, man.

David: this one was written intentionally to feature those two guys. I wrote it with the idea that both of them would play beautiful solos. And Ron said to me ‘you pass the melody from player to player all around the band’ and I said ‘yeah, there’s no reason not to’.

Jim: Well, that is the end of second CD, and now the third one. It’s amazing that we recorded 22 tunes (almost three hours of music) in just four days–and got everyone of them in the can with great great mixes, it’s just amazing!

Disc 3

Jim: FInally, the last disc–CD 3. It starts out with a new piece by you (that also has a tuba solo in it, thank you David), called Latka Variations.

David: I think what happened was there was no name for it, and somebody said ‘well what if you name it with another item on the menu at the deli down on Alvarado, Langer’s’. I had written one called Langer’s #19, the pastrami sandwich, so this tune became Latka. There’s no meaning behind it. My uncle Jack (after his wife died) would come around for dinner and my mother asked, “would you like another lakta?” And he would say ‘latka schmatka, as long as I have my health!’. I never forgot that.

Jim: I love your titles, just like I love jazz band.

David: It is a true variation, by the way, that’s the one thing I took from the classical studies. Everything in that chart is based on that original figure (sings) — those tones govern every action in the whole piece.

Jim: to me this is one of the most interesting uses of your polyphony, though it’s hard to pick that out.

Jim: The next one is by Harold Arlen, The Next Time the Dream’s on Me–and it swings like crazy.

David: Well I consider that to be one of the “West Coast” arrangements, and the form is something I like, which is to have three soloists each play a chorus, play fours or eights at the end, and keep going. What stands out to me on the arrangement are the fours between the arrangement and the soloists. There are four bars of the band and then four bars of the soloist, and this goes on for a while, and those four bar haikus, or vignettes, or whatever you want to call them, are built on the first four bars of the tune.

Jim: there are some brilliant fours played on that by Scott Whitfield, Jim Quam and Jonathan Dane!

David: Yeah, Scott Whitfield, wow,

Jim: So next is another original by you (a favorite of mine), one of your longer ones called Love Letter to Pythagoras.

David: There’s an ironic element in here, which is that I was planning on using the scale of pythagoras, which is like C major, except F is in the bass, it goes up in fifths, F C G D A E and B way up at the top. I was going to end with tha but I didn’t–I never got to it in the whole piece–I never got to Pythagoras. But I had a friend that I called Pythagoras, so he would like that. Yeah Love Letter to Pythagoras was supposed to be a ‘thank you for the beautiful sound that you brought to us’ but I never got to the sound, I just kept writing the music and it evolved by itself. It just started out typical slow and gets fast later. There’s one thing I wanted to mention. In this tune I paid tribute to Gary Mulligan, but only in the transitions between the two solos and the fast tempo. There are three transitions, and the first one sounds very close to Mulligan, and the second one was like me, and the third one was an example of what Mulligan influenced in me. And those three transitions are all about Mulligan.

Jim: The next tune is Waiting for a Train Part 2. Is there a part 1?

David: Yeah, it’s in the book

Jim: Well it’s another original, and it’s very interesting to me.

David; Well, it’s one of the few that I can listen to without saying ‘oh I’ve heard enough of that’. I still like it. It’s a mambo, and the title comes from when I was traveling between Lucerne, Switzerland and Schaffhausen. I was a 2 1/2 hour train trip, and then I had a forty minute wait for a regional train in Lucerne to get to my village where i lived. And that forty minutes in the winter, outside on a metal bench, was really something to remember. Anyway, I did a lot of waiting for trains, and I would get ideas. I would sit there and think ‘okay to pass the time I’ll write a chart in my head’ and that was one of them.

Jim: Well, another beautiful thing, and swinging like crazy with medium Latin.

David: well it’s Latin, but it’s more like a mambo than the others. The rhythm section was fantastic on all the Latin feels.

Jim: I agree, boy they laid it down, huh?

Jim: The next tune is called Dark Passage, another recent tune, and this features our baritone sax Bob Carr, Ron Stout on Flugel, John Chiodini, guitar, Scott Whitfield, Trombone and Susan Quam, Bass. (Like many of your charts you have several soloists).

David: I had the idea that Ron Stout could play that melody and I sort of wrote it around him.

Jim: One of the things I love about your band (and all jazz bands use this) is the sarcastic sense of humor we have. The puns are almost sickening. You wouldn’t believe how people pass these things around, and they have risque ideas about these things. There’s nothing like jazz musician humor.

David: There are some really funny little titles that came out of jazz tunes.

Jim: In my composition I’m influenced a lot by jazz titles, and I get pretty punny often too. It’s a fun part of writing.

Jim: Okay, we finish the album with another new tune by you–an original called L.A. Mysterioso.

David: When I last came back from Switzerland (I hadn’t had a vacation that year), so after maybe 15 months. When I got off the airplane and was driving back, I was shocked by the noise and the whole thing of L.A. It crunched on me. So I went home and wasn’t able to work for a few days, just adjusting, and I thought ‘I’m going to go ahead and write the feeling I had when I got back to LA, and all this noise and cars and everything, and so the harmony in there is quite different compared to everything else, but that was the feel I had. Then the other parts of that piece are the traffic, action movements, quickness.

Jim: And of course it’s the perfect album, because it just goes Boo Doo Dop!

David: And then the dog barks

Jim: Forgive me, on the end of all Basset Hound Music (my company) label CD I attach a ditty I call Dog Tags. it identifies me and my dogs, of course. It leaves them with a little humor.

David: It’s more poignant than you think! You’re right about the tune being perfect like that, but then at the end of the barking dog, a voice very similar to my own says ‘oh’, and that to me is the important part.

Jim: Well we chose that to put on the end, we thought it was so funny.

David: I have dogs around me that bark, and they drive me nuts, so in L.A. Mysterioso it just fits right in.

Jim: Well basset hounds go along with both of our personalities. They love music, and unfortunately I don’t have one anymore, but I had them for 50 years.

Jim: So we’re done with all the tunes, but I have about three more topics I would like to get on tape with you. Can you just briefly say something about Chris Zambon, who did our cover, and Kim Richmond, her husband, who was our tone-meister.

David: well Kim did a great job, I think the band responded to him beautifully, because he’s a great musician, and a model of West Coast composing. He did a great job coming out and taking care of business. He was so serious, and he applied all of his musical ability to this job. He really took it seriously, and I’m really grateful to him for taking a role that I should have been able to do, but I couldn’t, and he knew it, so he came out and kind of rehearsed things, reminded people of things, and corrected things–and it was great. As far as the picture, I love it! I would love to meet her some day–she must be a lovely woman to paint that way.

Jim: Chris is quite a famous painter in oil, acrylics, and abstracts and she captured the mood of the album.

David: I agree completely. I remember at the Old Union Hall in Hollywood, she had some paintings up in the old foyer, and I would like her to know that I used to stop and look at them for inspiration when I would rehearse. Two of them really touched me. I just love her paintings.

Jim: The last thing I wanted to mention was your Saxtet. I know you’re so proud of the group, and I want you to say something about it. And you’ve written a fair amount of classical music, including a Cello oncerto and an Oboe d’Amore concerto for Phil Feather. Please mention something about your classical music and your saxtet.

David: One thing about living in Europe all those years was I got to have pieces played. In L.A. they’re very conservative about modern composers, everyone has an opinion, and then in the end they don’t play anything except that mush where you just play the same thing over and over again. I don’t consider that music. I consider that wallpaper. I don’t consider composition to just be repetition like that. I can understand someone writing something like that at home and leaving it on the table. I used to write things like that, but I can’t imagine putting it out into a world where artistic music is supposed to be played. It doesn’t make sense to me. In Europe, they’re more broad-minded. They play more different kinds of music. I got to have a symphony played called The Rheinfall, and I had a cello piece called Rhapsody of Songs. The cellist was the first cellist in the Munich orchestra, and he wanted to do something like songs rather than a classical piece. He said ‘I would like you to arrange some songs by Gershwin, Cole Porter, and so forth for Cello and orchestra’ and the conductor said ‘well I know this man, why don’t you let him write his own songs?’ And I did, and that was the cello piece. There were several others too. I had a number of pieces played, and as you know I was teaching classical music, not jazz in Europe, so I had a lot of composers to deal with.

Jim: You have a broad palette, my friend. Can you say something about the Saxtet?

David: Well it started as a trio–with Bill Perkins, Steve Kravitz and me. One day, after seven years of playing at Perk’s house, we said ‘well what if we had two guys playing on each part?’ It would sound very different, and so we organized a rehearsal with two tenors, two altos, and two baritones, and the first rehearsal I brought in a piece for six saxophones in six parts, so it never turned out to be a double trio like I thought, it ended up being a sextet. I don’t know how many sextets we have in that book. We actually have two books. That group went on for a number of years, just six guys in a circle, and then one day Bob Cooper said ‘what if you wrote a piece with chord changes and a soloist?’ so suddenly the new group developed–which is the other book—for nine pieces: six saxophones plus guitar, bass, and drums. That book now has over 100 arrangements. The one with rhythm characteristically is a jazz book, and the six saxophones (acapella) is more classical in the sense of being compositions. But we never play like classical sax players, because we’re not that. We always play with a jazz feel, even if the music is written completely out, and has it’s own form without solos.

Jim: Well I hope I can help you document all this music, maybe get it recorded and get it preserved. It’s like your other rehearsal band, if you will, and you alternate off between a 13 piece band and a saxtet, and a lot of the same players play in both, but again your groups have featured the greatest players in Los Angeles as long as I can remember.

FINE